Many hospitals have adopted systems for interoperable patient data exchange and are connected to national networks. However, ONC has consistently found that rates of interoperable exchange for smaller, rural, and independent hospitals have notably lagged behind other hospitals. For example, in both 2017 and 2021, rural hospitals were 23 percentage points less likely to engage in interoperable exchange compared to urban hospitals. In a recent study, ONC explored this digital divide to better understand the relationship between interoperable exchange and measures of hospitals that served populations that have been marginalized.

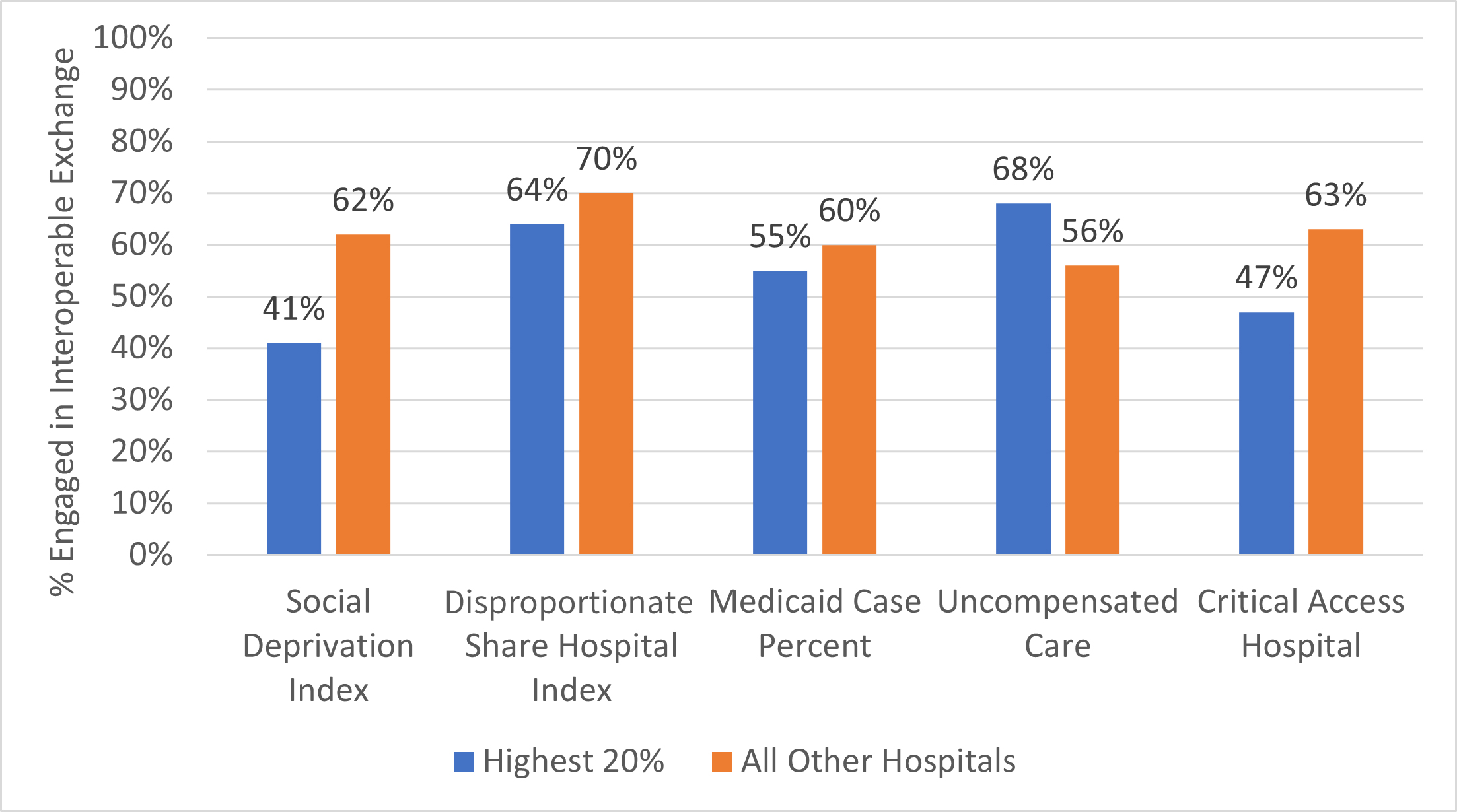

The figure below shows the differences in interoperable exchange by each of several available measures for the extent to which hospitals serve populations that have been marginalized. The 20% of hospitals that served ZIP Codes™ with the highest Social Deprivation Index (SDI) were 21 percentage points less likely to engage in interoperable exchange than the other 80% of hospitals, while critical access hospitals were 16 percentage points less likely than non-critical access hospitals. That divide was not evident based on other available metrics.

Differences in Hospital Engagement in Interoperable Exchange Based on Measures of Serving Populations that Have been Marginalized.

Notes: The “Highest 20%” refers to the 20% of hospitals with the highest value on each measure related to the population served (e.g., 20% of hospitals with the highest SDI in the first two bars; 20% of hospitals with the highest DSH Index in the next two). Engagement in Interoperable Exchange is defined as sending, receiving, finding, and integrating information from outside organizations.

How Interoperability Could Help Marginalized Populations

Populations that have been marginalized are at higher risk for fragmented, poorly coordinated care and may therefore stand to benefit substantially from interoperable exchange by the organizations that serve them. For example, these populations are more likely to rely on emergency departments (EDs) for care and more likely to visit multiple facilities. When a patient arrives at an ED that does not have electronic health information from the patient’s most recent doctor’s visit or prior ED stay across town, that patient is at higher risk of redundant diagnostic procedures, medication discrepancies, and discordant diagnoses. This may increase the time and cost of care, as well as increase the chance for errors due to providers not knowing potentially important information like the patient’s allergies and current medications.

Identifying Where Interoperability and Equity Intersect

A fundamental challenge we identified while investigating this question is that there are several ways to identify hospitals that disproportionately treat economically and socially marginalized populations. In our research, we assessed four ways based upon key federal, state, and local government programs:

- Medicaid caseload

- Medicare Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) Index

- Uncompensated care burden

- Critical Access Hospital (CAH) designation

We also assessed a fifth measure: the Social Deprivation Index (SDI). A relatively new type of measure, SDI draws on US census data about social drivers of health that collectively reflect the relative deprivation of a geographic area and its residents – and that have been validated to predict health outcomes better than poverty alone.

What Do the Data Tell Us?

In initial analysis—and similar to the work of others—we found that these five measures identified overlapping but clearly distinct sets of hospitals. Of the five measures, only the SDI consistently identified a difference in interoperability. This difference was observed when we examined the likelihood that a hospital engaged in interoperable exchange and the likelihood that hospitals participated in a national network; when we separately focused only on urban and only on rural hospitals; and after accounting for other hospital characteristics.

While we cannot directly explain why a persistent digital divide was identified by one measure but not by others, we believe there are two likely explanations.

One is that the SDI measure more effectively identifies hospitals that treat communities that have been marginalized by capturing broader dimensions of the area’s socioeconomic condition, and that these broader conditions are strongly related to a hospitals’ investment in interoperability.

A second, potentially complementary, explanation is the success of past programs that used programmatic measures to target support for hospitals to increase electronic health record (EHR) adoption. For example, the EHR Incentive Program (now Medicare Promoting Interoperability Program) operated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) allowed for additional payments to hospitals whose case volume was at least 10% Medicaid. Similarly, DSH funds ONC’s Regional Extension Centers, which worked with CAHs, and other federal programs may be responsible for higher rates of interoperability among hospitals identified by the programmatic proxies.

These findings indicate that relying on a single proxy could lead policy makers to focus on only a subset of hospitals that serve populations that have been marginalized and perhaps inadvertently exclude hospitals that also need it. Further evaluation of these and other proxy measures will be important to help policymakers at the federal, state, and local level effectively reduce disparities in who benefits from the proper flow of health information.