An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov

A

.gov

website belongs to an official government organization in the

United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A

lock

(

) or

https://

means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive

information only on official, secure websites.

Interoperability Among Office-Based Physicians in 2015 and 2017

No. 47 | May 2019

The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) declares it a national objective to achieve widespread interoperability through the use of certified electronic health records (EHR) and requires the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to measure the extent to which this objective is being met. Assessing the proportion of health care providers who electronically engage in the four domains of interoperability (sending, receiving, finding, and integrating health information received from outside sources) and use that information to inform clinical decision-making provides a means to assess progress towards reaching that objective. Using nationally representative surveys conducted in 2015 and 2017, this brief describes interoperability across office-based physicians, including who providers exchange information with; the types of information exchanged; and how interoperability varies among physicians.

Highlights

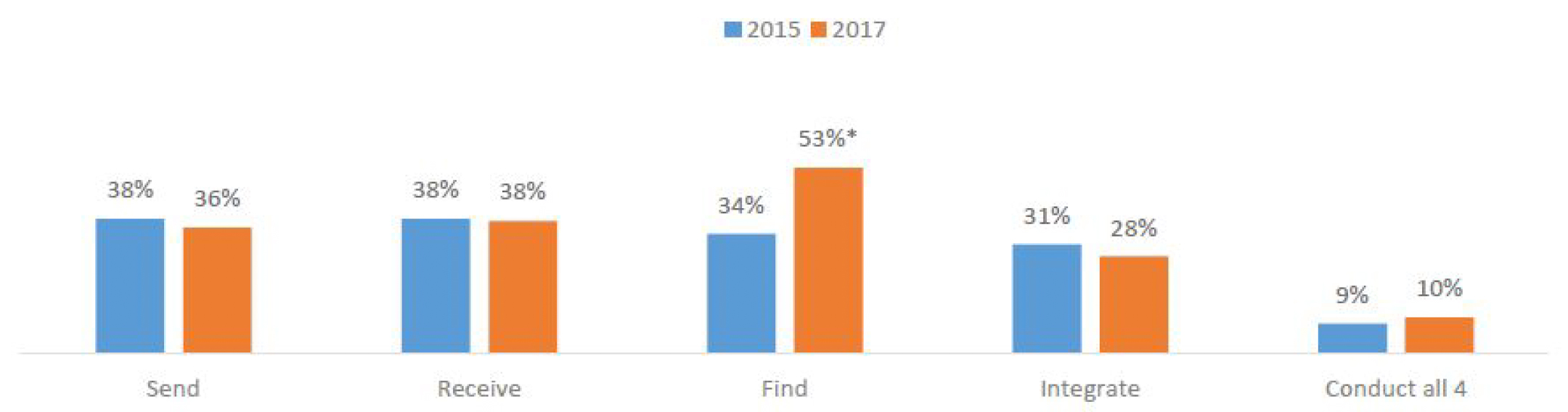

- Physicians’ rates of electronically finding or querying data from outside sources increased by 50% between 2015 and 2017; however, rates of engaging in other domains of interoperability did not change during this period.

- Physicians who used certified EHRs and participated in value-based payment models had higher rates of engaging in each of the 4 domains of interoperability compared to their counterparts.

- Among physicians who engaged in all 4 domains of interoperability, 8 in 10 had patient health information electronically available at the point of care in contrast to one-third of physicians nationally.

- About 1 in 5 primary care physicians electronically received emergency department notifications in 2017.

Physicians’ rates of electronically finding or querying patient health information from outside sources increased by 50% between 2015 and 2017.

Figure 1: Percentage of office-based physicians engaged in interoperable exchange (send, receive, find, integrate) of patient health information from outside sources, 2015-2017.

- Physicians’ engagement in electronically sending, receiving, and integrating information received from outside sources did not change between 2015 and 2017.

- In both 2015 and 2017, about only 1 in 10 physicians engaged in all 4 domains of interoperability.

Physicians who used certified EHRs and participated in value-based payment models had higher rates of engaging in each of the 4 domains of interoperability compared to their counterparts.

Table 1: Proportion of physicians that electronically send, receive, find and integrate patient health information by characteristic1 , 2017.

| Characteristics | Send | Receive | Find | Integrate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Health Record Status | ||||

| Certified EHR(ref) | 43% | 44% | 57%^ | 33%^ |

| Not Using Certified EHR | 7%* | 12%* | 35%^* | 5%* |

| Value-Based Payment Participation2 | ||||

| Participant (ref) | 46% | 47% | 61%^ | 33%^ |

| Not a participant | 23%^* | 26%* | 43%^* | 21%* |

| Specialty | ||||

| Primary Care (ref) | 37% | 39% | 61%^ | 30% |

| Surgical Specialists | 36% | 40% | 39%* | 28% |

| Medical Specialists | 33% | 34% | 50%^* | 24% |

| Ownership | ||||

| Physician/Group Practice (ref) | 31% | 32% | 54% | 27% |

| Insurance Company or HMO | 40% | 42%* | 54% | 28% |

| Community Health Center | 43% | 46% | 55% | 19% |

| Medical or Academic Health Center or Other Hospital | 46%* | 52%* | 47% | 32% |

| Practice Size | ||||

| 11 or more (ref) | 48% | 54% | 60% | 34% |

| 4 to 10 | 40% | 41%* | 55% | 31% |

| 2 to 3 | 32%* | 32%* | 54% | 25%* |

| Solo | 23%* | 22%* | 41%* | 20%* |

| Independent Practice Association (IPA) or Physician Hospital Organization (PHO) | ||||

| No (ref) | 28% | 31% | 50% | 24% |

| Yes | 39%* | 42%* | 55% | 29% |

Notes: 1 Denominator of estimates are consistent across a row; thus among physicians with a characteristic (row %). * indicates statistically different (p<0.05) from reference (ref) category. ^Refers to significant increase by category between 2015 and 2017 (p<0.05). 2 Participant in value-based payment refers to participation in one or more of the following initiatives: accountable care organizations, patient centered medical home or pay-for-performance. Data not shown but there were no differences in engaging in interoperability between rural or urban practice locations in 2017.

- Six times as many physicians with certified EHRs electronically sent patient health information to outside providers compared to those who did not have a certified EHR.

- Two times as many physicians who participated in value-based payment electronically sent and received patient health information with outside providers compared to those who did not participate.

- Physicians who worked in smaller practices (e.g., less than 3 physicians) or were not part of IPA/PHO had lower rates of electronically sending and receiving patient health information compared to their counterparts.

- Compared to 2015, in 2017 a higher percentage of physicians with certified EHRs electronically found or queried for patient health information from outside sources or providers.

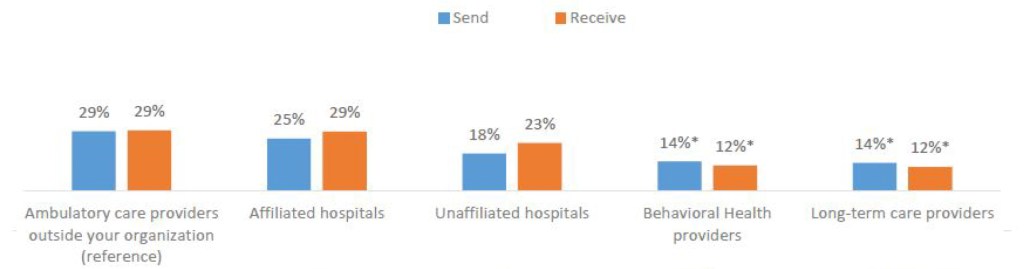

About 3 in 10 physicians electronically sent patient health information to ambulatory care providers outside their organization in 2017.

Figure 2: Physicians’ rate of electronically sending and receiving patient health information by exchange partner, 2017

Note: Unadjusted national estimates. * Physicians’ rate of send/receive is significantly different compared to rate of send/receive with ambulatory care providers outside organization (p- value <0.05).

- About 3 in 10 physicians electronically received patient health information from ambulatory care providers outside their organization.

- A similar percent of physicians electronically received patient heath information from ambulatory providers and affiliated and unaffiliated hospitals

- Twice as many physicians’ electronically sent patient health information to ambulatory care providers compared to long-term care (29% vs. 14%) or behavioral health care providers (29% vs. 14%).

- The percent of physicians’ who electronically received patient health information from ambulatory care providers was twice as high as the percent of physicians who received patient health information from long- term care (29% vs. 12%) or behavioral health care providers (29% vs. 12%).

Physicians electronically received and queried for medication-related information and imaging reports at higher rates in 2017 compared to 2015.

Table 2: Proportion of office-based physicians who electronically send, receive, and find/query different types of information, 2015 and 2017.

| Data or document type | Send | Receive | Find | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2017 | Diff (*) | 2015 | 2017 | Diff (*) | 2015 | 2017 | Diff (*) | |

| Summary of care Record | 21% | 24% | – | 25% | 29% | * | N/A | N/A | – |

| Medication lists | 27% | 29% | – | 26% | 31% | * | 24% | 35% | * |

| Patient problem lists | 25% | 27% | – | 23% | 28% | * | 25% | 27% | – |

| Medication allergy lists | 25% | 28% | – | 24% | 30% | * | 20% | 30% | * |

| Imaging reports | 23% | 25% | – | 29% | 34% | * | 36% | 48% | * |

| Laboratory results | 27% | 28% | – | 37% | 40% | – | 37% | 48% | * |

Notes: * Significant difference between 2015 and 2017 (p-value<0.05)

- Almost half of physicians queried for laboratory results from external sources or providers in 2017; this represented over a 30% increase between 2015 and 2017.

- Rates of sending different types of health information did not vary between 2015 and 2017.

- Laboratory results were the most common type of information electronically received and queried by physicians in both 2015 and 2017.

- Electronic sending of summary of care records remained the same between 2015 and 2017 but receipt of summary of care records increased by 16% during this period to 29%.

About 1 in 5 primary care physicians electronically received ED notifications in 2017.

Table 3: Office-based physicians’ rates of electronically exchanging data and documents related to public health, patients and emergency department (ED) and hospital settings, 2017

| Data or document type by setting | Send | Receive | Find |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exchange of Public health data | |||

| Public health registry data (e.g., immunizations, cancer) | 21% | 21% | — |

| Clinical registry data | 14% | 14% | — |

| Vaccination history queried by primary care physicians | — | — | 42% |

| Patients | |||

| Patient-generated data (e.g. data from self-monitoring devices) | — | 6% | — |

| Advance directives | — | — | 20% |

| Receipt of Documents from Hospitals | |||

| Hospital discharge summaries received by primary care physicians | — | 23% | — |

| ED notifications received by primary care physicians | — | 21% | — |

Notes: Office-based physicians do not send patient-generated health data, hospital discharge summaries or ED notifications; they only receive these types of data.

- Almost one-quarter of primary care physicians electronically received hospital discharge summaries.

- One-fifth of physicians electronically sent and received public health registry data.

- Over one in 10 physicians electronically sent and received data with clinical registries.

- About 4 in 10 of primary care physicians electronically searched for vaccination history data.

- About 1 in 5 physicians electronically queried or searched for advance directives.

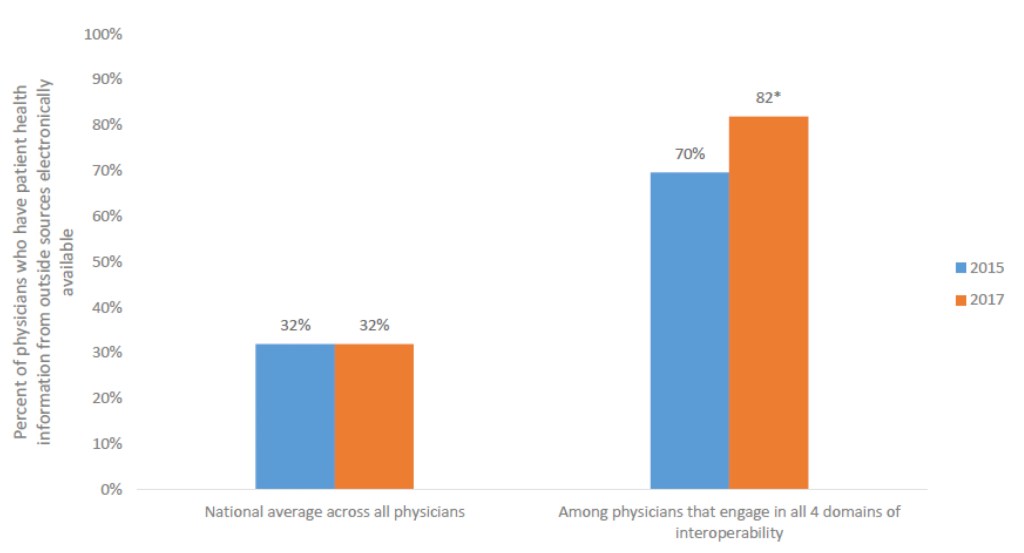

Among physicians who engaged in all 4 interoperability domains (send, receive, find, and integrate), 8 in 10 reported patient health information from outside sources was electronically available in 2017.

Figure 4: Percentage of physicians who have patient health information from outside encounters electronically available at the point of care by whether they engage in all 4 domains of interoperability (send, receive, find, and integrate) vs. national average, 2015 and 2017.

Notes: * Significant difference between 2015 and 2017 (p-value<0.05). Considered to have necessary information available if they “often” or “sometimes” had information from those outside encounters electronically available at the point of care when treating patients previously seen by other providers outside their organization. Electronically available does not include scanned or PDF documents. See Definitions for explanation of measures related to patient health information and summary of care records.

- In both 2015 and 2017, about one-third of physicians indicated that patient health information from outside sources was electronically available at the point of care.

- In both 2015 and 2017, physicians who engaged in all 4 domains of interoperability (send, receive, find, integrate) were over two times as likely to have patient health information from outside sources compared to the national average.

- Among physicians engaged in all 4 interoperability domains, a higher percentage reported that they had patient health information from outside sources electronically available in 2017 compared to 2015.

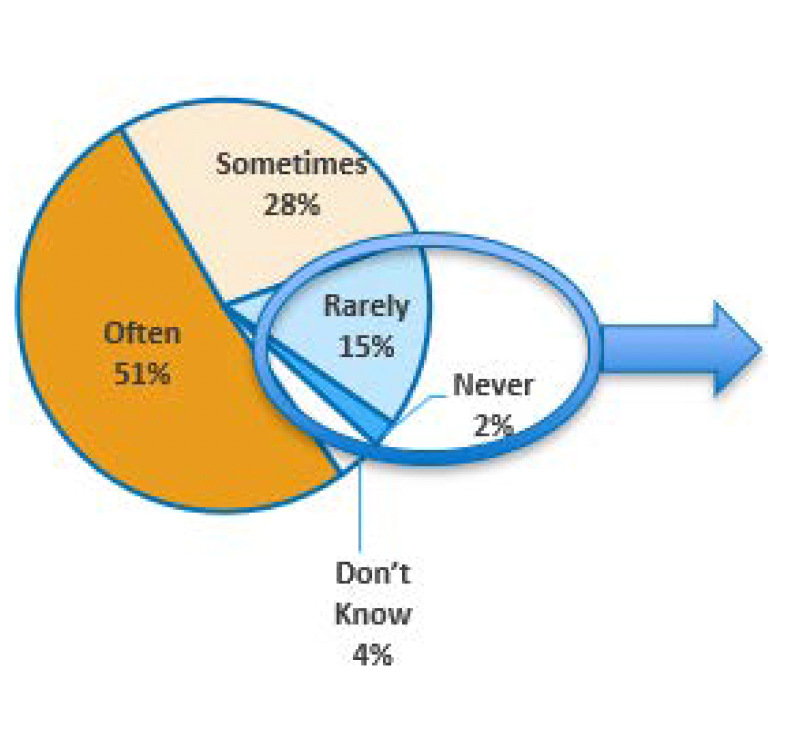

Among the 38% of physicians that electronically received patient health information from outside providers (figure 1), three-quarters used the information sometimes or often for clinical decision- making.

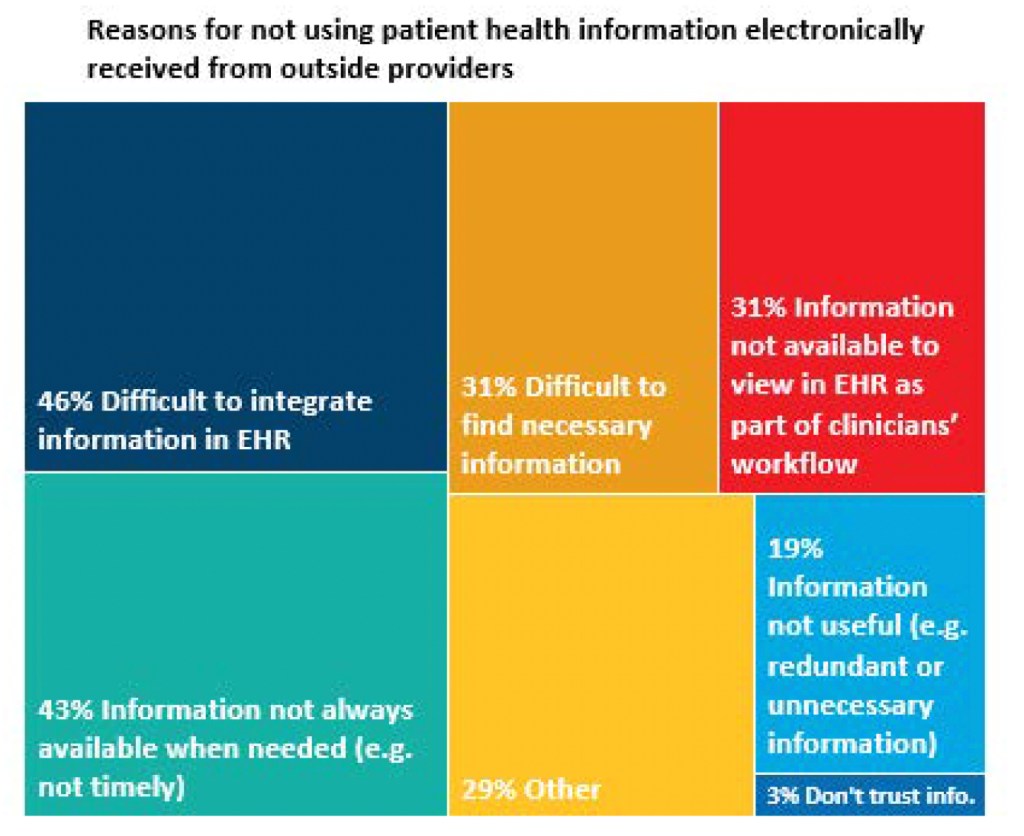

Figure 5: Frequency of using electronic information received from outside sources (among physicians that electronically receive patient health information) and Reasons for not using patient health information electronically received (among those that rarely/never use information).

Notes: Denominator of Frequency of Use (left graphic) limited to physicians who electronically receive information (38% of all physicians), See Figure 1 Denominator for right graphic limited to physicians who rarely or never use information they receive electronically (17% of those who electronically received information, or about 7% of all physicians).

- Among the 38% of physicians who electronically received patient health information, almost one in five physicians (17%) rarely or never used that information to inform clinical decisions.

- The top two reasons for rarely or never using patient health information electronically were related to difficulty integrating information into the EHR and the information not available when needed.

- Half of physicians who electronically received patient health information used it often to inform clinical decisions.

- Among physicians who rarely or never used patient health information they electronically received, three in ten indicated either that the information was not available to view in their EHR or that it was difficult to find the necessary information.

- Very few physicians reported lack of trusting the information as a reason for not using the information they electronically received from an outside provider or source.

Summary

Interoperability among office-based physicians was relatively constant between 2015 and 2017. Physicians’ rates of querying or finding patient health information from outside sources increased by 50 percent. However, despite this growth, physicians’ rates of engaging in the other interoperability domains (send, receive, and integrate) remained the same between 2015 and 2017. Only about 1 in 10 physicians engaged in all 4 interoperability domains during these years. The proportion of physicians (32%) reporting that they have patient health information electronically available from outside sources also did not change during this period. However, similar to hospital settings, physicians who engaged in all 4 domains were more likely to have patient health information electronically available from outside sources at the point of care (3).

A majority of physicians did not electronically receive clinical data during patients’ transitions of care. More physicians electronically received summary of care records in 2017 compared to 2015. However, in 2017, only about 3 in 10 physicians electronically received summary of care records. One in 5 primary care physicians electronically received ED notifications, and one-quarter of primary care physicians electronically received hospital discharge summaries. Both of these types of information could be used by physicians to follow-up with their patients. These rates may increase if CMS’ proposed rule on interoperability—which would require Medicare-participating hospitals to send electronic notifications when a patient is admitted, discharged or transferred— is finalized (4).

Overall, among the 38% of physicians who electronically received patient health information in 2017, three-quarters used that information sometimes or often to inform clinical decisions. Physicians who rarely or never used information they electronically received, reported a number of barriers to using this information. The key barriers cited include: lack of integration of data into their EHRs; limited information available when needed; poor clinical workflow and difficulty finding the information. Hospitals identified a similar set of barriers to usage (3).

Moreover, similar to hospitals, the limited capabilities of exchange partners are barriers to exchange for physicians (3). Physicians had lower rates of exchange (e.g., send/receive) with providers not eligible for the CMS EHR Incentive Program; such as long-term care and behavioral health providers compared to ambulatory care providers. In contrast, physician’s rates of exchange did not differ by hospital affiliation or between ambulatory care providers and hospitals.

Interoperability also varied by a number of practice characteristics. Compared to their counterparts, physicians who had a certified EHR or participated in some type of value-based payment models (e.g., accountable care organization, Patient-Centered Medical Home or P4P program) had higher rates of engaging in all 4 interoperability domains. Physicians who worked in smaller practices or were not owned or part of a larger organization, had lower rates of electronically sending and receiving patient health information compared to those who worked in settings with access to greater resources.

Progress is needed to ensure that all physicians are able to use interoperable health IT systems. However, these data indicate the expanded use of advanced certified EHR technology should improve physicians’ ability to engage in interoperability and access information they need at the point of care (5). Greater participation in initiatives such as the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) or alternative payment models (APMs) should improve interoperability. These programs incentivize the electronic sharing of health information across providers and promote the use of the 2015 Edition certified EHR technology. (1,6,7). Furthermore, the 21st Century Cures Act calls for enabling interoperable exchange through health information networks and by making patient health information more accessible through application programming interfaces (APIs) (8). As currently drafted, the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA) should expand the availability of qualified health information networks that provide a common set of exchange services for a reasonable cost (9). This would enable physicians working in practices with fewer resources as well as health care providers not eligible for the EHR Incentive Program to more easily participate and electronically exchange health information. ONC’s recent proposed rule related to the 21st Century Cures Act promotes the use of secure, standard-based APIs that make patient health information electronically available through health applications (apps) (10). As proposed, patients and providers should be able to more easily access and use electronic patient health information. Together, these initiatives have the potential to increase interoperability across office-based physicians to achieve the goals set forth by MACRA.

Definitions

Send patient health information: The use of an EHR or web portal to send patient health information to other providers and public health agencies outside their medical organization.

Receive patient health information: The use of an EHR or web portal to receive patient health information from other providers and public health agencies outside their medical organization.

Send summary of care of record: Electronically send summary of care records to providers outside their medical organization including public health agencies. Electronically sending does not include eFax, fax, or paper-based methods.

Receive patient health information: Electronically receive summary of care records from providers outside their medical organization including public health agencies. Electronically receive does not include eFax, fax, or paper-based methods.

Find or Query patient health information: Physicians electronically searching for health information from sources outside of their medical organization when seeing a new patient or an existing patient who has received services from other providers either “always”, “often” or “sometimes”.

Integrate patient health information: A composite measure which reports on the ability of physicians to integrate various types of health information electronically received from other providers into an EHR without special effort like manual entry or scanning. Types of data include those listed in Table 2 (this includes summary of care records).

Integrate summary of care record: The ability of physicians to integrate summary of care records electronically received from other providers into an EHR without special effort like manual entry or scanning.

Electronic Availability of Outside Information: When treating patients seen by other providers outside their medical organization, physicians or their staff have clinical information from those outside encounters electronically available “always” or “sometimes” at the point of care. Electronically available does not include scanned or PDF documents.

Certified EHR: Physicians indicated that their reporting location used an EHR, and that EHR met the criteria for Meaningful Use.

Data Source and Methods

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics conducts the National Electronic Health Records Survey (NEHRS) survey on an annual basis. Physicians included in this survey provide direct patient care in office-based practices and community health centers; excluded are those who do not provide direct patient care (radiologists, anesthesiologists, and pathologists). Additional documentation regarding the survey is here: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/ahcd_survey_instruments.htm

Reference

1. The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA), (Pub. L. No. 114 – 10, enacted April 16, 2015), Section 106(b)(1). https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-114publ10/html/PLAW-114publ10.htm.

2. Connecting Health and Care for the Nation: A Shared Nationwide Interoperability Roadmap Version 1.0. https://www.healthit.gov/policy-researchers-implementers/interoperability

3. Patel V., Henry J., Pylypchuk Y., & Searcy T. (May 2016). Interoperability among U.S. Non-federal Acute Care Hospitals in 2015. ONC Data Brief, no.36. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology: Washington DC. https://healthit.gov/data/data-briefs/interoperability-among-us-non-federal-acute-care-hospitals-2015/

4. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid. CMS Advances Interoperability & Patient Access to Health Data through New Proposals. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/cms-advances-interoperability-patient-access-health-data-through-new-proposals

5. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (October, 2015). 2015 Edition Health Information Technology (Health IT) Certification Criteria, 2015 Edition Base Electronic Health Record (EHR) Definition, and ONC Health IT Certification Program Modifications. Federal Register. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2015/10/16/2015-25597/2015- edition-health-information-technology-health-it-certification-criteria-2015-edition-base

6. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. MACRA: Delivery System Reform & Delivery Payment Reform. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/quality/value-based-programs/chip-reauthorization-act

7. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Program; Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and Alternative Payment Model (APM) Incentive under the Physician Fee Schedule, and Criteria for Physician-Focused Payment Models, Final Rule with Comment Period. October, 14 2016. https://hhs.com/assets/docs/CMS-5517-FC.pdf

8. 21st Century Cures Act, section 4006. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-114publ255/pdf/PLAW-114publ255.pdf

9. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Draft Trusted Exchange Framework. https://healthit.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/draft-trusted-exchange-framework.pdf

10. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Notice of Proposed Rulemaking to Improve the Interoperability of Health Information. https://www.healthit.gov/topic/laws-regulation-and-policy/notice-proposed-rulemaking-improve-interoperability-health

Acknowledgements

The authors are with the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. The data brief was developed under the direction of Mera Choi, Director of the Technical Strategy and Analysis, and Talisha Searcy, Branch Chief of the Data Analysis Branch.

Suggested Citation

Patel V, Pylypchuk Y, Parasrampuria S & Kachay L. (May 2019) Interoperability among Office-Based Physicians in 2015 and 2017. ONC Data Brief, no.47. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology: Washington D.C.